We are the authors of Q, 54, Manituana, Altai and other historical novels, a form that we practised for many years, until we decided to move on and use history in other ways.

The last historical novel in the sequence we had started in the 1990s was L’armata dei sonnambuli (2014), which already announced changes.

Since then, we’ve been drawing lessons from what we learnt from exploring that genre and forcing its conventions, and engage in new experiments.

For instance, we seek an uncanny balance between a careful historical reconstruction and the exploration of fantastic dimensions, which for us include the visionary, the dreamlike, the psychedelic, the mythological, the supernatural.

This is what we tried to do, in various ways, in L’invisibile ovunque (2015), Proletkult (2018), La macchina del vento (2019), UFO 78 (2022), La vera storia della Banda Hood (2024) and Gli uomini pesce (2024).

Our full bibliography (the original Italian editions) can be found here.

N.B. Many of the books we wrote in the 2010s and 2020s are also available in French, German, Spanish (Castilian), Catalan, Greek and a few other languages. Unfortunately, as of May 2025, none of them have been translated into English.

The band and its members

At various stages in its history, the band had four, five and again four members. As of 2015, we are a trio. Each of us also writes books ‘solo’, but the expression fails to make the point: for us, they are all Wu Ming works, whether they are written by the whole ensemble or not. They are part of a collective enterprise, productions of our craft workshop.

It is to signal this that each of us incorporates the name of the group in his pen name: Wu Ming 1, Wu Ming 2 and Wu Ming 4. The numbering follows the alphabetical order of our surnames: (Roberto) Bui, (Giovanni) Cattabriga and (Federico) Guglielmi. Luca Di Meo (2000 to 2008, who passed away in 2023) and Riccardo Pedrini (2000 to 2015) were also part of the group.

Noms de plume

As you can see, our legal names are not secret. It simply does not make sense to use them when writing about our books or referring to our work in various ways. In our literary and cultural activity, like so many before us, we adopt noms de plume. Pen names that refer to the collective project (Wu Ming) and are an essential part of our poetics.

An essential part of that poetics is our policy on public image.

Flesh and bone

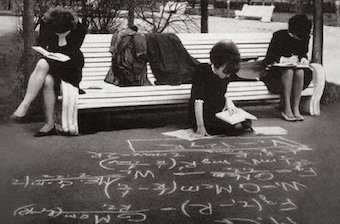

We try to avoid photos and videos, we never appear on TV, we kindly ask not to publish pictures of our faces. We try to appear only live, in the flesh, in the least techno-mediated way possible. If someone recognises us in the street, it means they have been to one of our presentations, readings, workshops, seminars, treks or whatever. Their body shared a place and a concrete experience with ours.

If you happened to see pictures of us, there are two cases: either they’re other people – there’s no shortage of misattributions on the net – or the photo was spread without our knowledge and against our express wish that this should not happen.

From Luther Blissett to Wu Ming

Our first novel, Q, came out in 1999 under the name Luther Blissett, in compliance with the rules of the project we were carrying out. The Luther Blissett Project, in fact. Which ended that very year. Since 2000, we have been called Wu Ming.

Why a Chinese name? After a quarter of a century, the reasons, whatever they were, no longer matter much. Suffice it to say that ‘Wu Ming’ (无名) has these meanings.

From Giap to the Wu Ming Foundation

This site is called Giap and has been on line since April 2010. It takes its name from the email newsletter we used to send out in the noughties, which at a certain point had 12,000 subscribers. For reasons that would take too long to explain here (it was an allegory), the newsletter was named after the Vietnamese general Vo Nguyen Giap (1911-2013). The matter is explained here, in the paragraph titled ‘Dien Bien Q’. Alas, it’s in Italian.

Over the years, Giap has become a veritable laboratory of research, plural writing and enquiry, and has infused and reshaped our work.

Thanks to Giap, a larger plural subject has developed around us, the Wu Ming Foundation. There was a description of it that we updated until 2023, but it was too long by then, so we archived it and you can read it here.

Giap is – not exclusively, but mainly – in Italian. If you’re interested in stuff by or about us in other languages, please check out our multilanguage Telegram channel and/or our multilanguage news aggregator on Tumblr.

How to contact us

Here.

–

–