by Florian Cramer and Wu Ming 1

QAnon – the movement according to which Donald Trump wages a secret war against satanic and pedophilic elites – is not just a run-of-the-mill conspiracy belief, but functions as a collective text interpretation game. This is also the reason for his ridiculous success, which now includes the German Reichsbürger [people who believe that the German Reich still exists and that the Federal Republic of Germany is a company with no legal basis registered in Frankfurt] and the Corona denier scene. The fact that QAnon’s origin story was collaged from literary and popular cultural sources – among them a collective novel published in 1999 also by the co-author of this article – does not throw off its followers.

“QAnon” began in the fall of 2017 with a series of fragmentary messages from a user “Q” on the Internet forum 4chan, one of the few remaining unregulated places on the Internet on which the masked “Anonymous” movement had emerged in the early 2000s. At the latest in 2014, when a hate mob formed there against a feminist computer game developer, it slid into militant sexism, racism and anti-Semitism. 4chan became one of the headquarters of the extreme right-wing “Alternative Right” (“Alt-Right”). In 2016, in the final phase of Trump’s election campaign, the Alt-Right spread the conspiracy fantasy “Pizzagate”: In the basement of a Washington pizzeria, high-ranking representatives of the Democratic Party supposedly imprisoned children as sex slaves. A “Pizzagate” supporter stormed the place with a rifle to discover that it didn’t even have a basement.

The fantasy only seemingly collapsed. A year later, the belief in a pedophile world conspiracy of liberal elites, including Hillary Clinton and George Soros, was revived in the cryptic messages of the alleged secret agent “Q” on 4chan. Its narrative – that Trump is secretly conducting an apocalyptic final battle against a pedophile and satanic world elite who drink children’s blood to keep themselves young – picks up on anti-Semitic myths that were already circulating in the Middle Ages. In press interviews, Trump encourages this belief by refusing to distance himself from QAnon. At least 25 Republican Party congress candidates are connected with the QAnon subculture. QAnon Facebook groups had more than three million members. During the attempted storming of the Reichstag during the Berlin “Lateral Thinkers” Corona denier protests, a large QAnon flag was being waved.

In Germany and its neighbouring countries like the Netherlands, QAnon spread extremely fast in the milieu of esoteric and extreme right-wing Corona deniers. Its tales of the devil-worshipping and child blood drinking elites are also spread by well-known influencers in the scene such as the pop singer Xavier Naidoo. In Italy, the QAnon myth has turned desperate and economically ruined people into Corona deniers by providing absurd answers to legitimate questions about how the government has dealt with this emergency.

A world conspiracy mapping developed within QAnon lists – besides Trump, Clinton and Soros – all other usual suspects such as the Illuminati, JFK and Nostradamus. QAnon has thus grown into a super-conspiracy fantasy that attempts to integrate all conspiracy fantasies into the construction of an alternative world and a political theology.

Those who grew up in sub- and counter-cultures of the 1960s to 1990s will find much of this cartography familiar. It lists some of the same actors and spins similar all-encompassing cross-connections as, for example, the 1975 novel trilogy Illuminatus! by Robert Shea and Robert Anton Wilson. Illuminatus!, in turn, quotes Thomas Pynchon‘s 1967 novel The Crying of Lot 49, whose heroine tracks down a seemingly ubiquitous underground postal system called Tristero, which amounts to an alternative reality of American countercultre. Tristero’s existence, however, remains unclear until the end of the novel, and its parallel world is not a promised land, since extreme right-wing groups are also part of it.

Those who grew up in sub- and counter-cultures of the 1960s to 1990s will find much of this cartography familiar. It lists some of the same actors and spins similar all-encompassing cross-connections as, for example, the 1975 novel trilogy Illuminatus! by Robert Shea and Robert Anton Wilson. Illuminatus!, in turn, quotes Thomas Pynchon‘s 1967 novel The Crying of Lot 49, whose heroine tracks down a seemingly ubiquitous underground postal system called Tristero, which amounts to an alternative reality of American countercultre. Tristero’s existence, however, remains unclear until the end of the novel, and its parallel world is not a promised land, since extreme right-wing groups are also part of it.

Wilson and Shea’s Illuminatus!, on the other hand, plays with conspiracy myths in carefree pop-cultural ways.

Illuminatus! became a cult book among computer hackers, among others. Since hackers occupy themselves with systems and system interconnections in the broadest sense, their subculture has had a traditional affinity both with factually substantiated conspiracy theories and with conspiracy speculation. It is therefore likely that the person or the people who, under the moniker of “Q”, fuel the conspiracy myth with their text fragments, come – like 4chan itself – from the larger orbit of this subculture.

Illuminatus! became a cult book among computer hackers, among others. Since hackers occupy themselves with systems and system interconnections in the broadest sense, their subculture has had a traditional affinity both with factually substantiated conspiracy theories and with conspiracy speculation. It is therefore likely that the person or the people who, under the moniker of “Q”, fuel the conspiracy myth with their text fragments, come – like 4chan itself – from the larger orbit of this subculture.

Since the emergence of the “Alt-Right”, 4chan and its newer counterpart 8chan/8kun no longer only serve computer-savvy “shit posters” for malicious pastimes, but its political memes spill over into the mainstream social networks where they reach gullible people who have affinities to evangelical revivalist movements in the USA, respectively to the right-wing esoteric scene in Europe. The QAnon documents literally continue Christian fundamentalism by promising, in the same words as the American evangelical movements of the 18th century, a “Great Awakening” and an imminent final battle of good against evil.

At least one source of the QAnon myth is very likely: the Italian novel Q, published in 1999 and co-written by one of the two authors of this article as a member of the writers collective Luther Blissett. It was published in more than thirty countries, including German and English translations. The novel is set in the Reformation period and tells the story of a secret agent who spreads disinformation messages under the name “Q” and – just like the Q of “QAnon” – claims to have access to the highest political power and secret information. In the novel, Q’s letters persuade Thomas Müntzer’s Protestant peasant warriors to fight a battle in Thuringia in order to expel aristocrats and bishops for good. This battle however turns out to be a deadly trap. The “Q” of QAnon plagiarizes this, too, when he claims that the “storm” of a final battle is imminent, in which Trump will liberate the USA from the “Deep State” and the liberal elites.

At least one source of the QAnon myth is very likely: the Italian novel Q, published in 1999 and co-written by one of the two authors of this article as a member of the writers collective Luther Blissett. It was published in more than thirty countries, including German and English translations. The novel is set in the Reformation period and tells the story of a secret agent who spreads disinformation messages under the name “Q” and – just like the Q of “QAnon” – claims to have access to the highest political power and secret information. In the novel, Q’s letters persuade Thomas Müntzer’s Protestant peasant warriors to fight a battle in Thuringia in order to expel aristocrats and bishops for good. This battle however turns out to be a deadly trap. The “Q” of QAnon plagiarizes this, too, when he claims that the “storm” of a final battle is imminent, in which Trump will liberate the USA from the “Deep State” and the liberal elites.

The parallels between Luther Blissett’s Q and QAnon already caught the attention of the two authors of this article in 2018. American news media reported it. Obviously, this couldn’t shake the QAnon belief.

The way in which Luther Blissett’s Q was cribbed for QAnon is reminiscent of another fake document: the anti-Semitic Protocols of the Elders of Zion, which appeared in 1903, allegedly documenting a Jewish world conspiracy, but which in fact were compiled and rewritten from other texts, including an anti-monarchist satirical novel by the former Paris Communard Maurice Joly published in 1886.

This fact is also mentioned in Umberto Eco‘s 1988 novel Foucault’s Pendulum, with a note on the British anti-Semite and fascist Nesta Webster, who had interpreted the textual similarities between Joly’s novel and the Protocols as an indication that Joly was privy to the conspiracy. (This is probably how QAnon believers would also interpret Luther Blissett’s Q.) Foucault’s Pendulum is, after The Crying of Lot 49 and Illuminatus!, another literary compendium of conspiracy myths, but with the clearest educational impetus. It is about three men who, on a whim, construct a conspiracy myth by combining information and legends about historical secret societies and occultist movements, but in the process become more and more enmeshed in their game and end up waking up actual political conspirators. The secret document they try to decipher – and whose fragmentary nature anticipates the QAnon messages on 4chan – turns out to be a banal shopping list.

This fact is also mentioned in Umberto Eco‘s 1988 novel Foucault’s Pendulum, with a note on the British anti-Semite and fascist Nesta Webster, who had interpreted the textual similarities between Joly’s novel and the Protocols as an indication that Joly was privy to the conspiracy. (This is probably how QAnon believers would also interpret Luther Blissett’s Q.) Foucault’s Pendulum is, after The Crying of Lot 49 and Illuminatus!, another literary compendium of conspiracy myths, but with the clearest educational impetus. It is about three men who, on a whim, construct a conspiracy myth by combining information and legends about historical secret societies and occultist movements, but in the process become more and more enmeshed in their game and end up waking up actual political conspirators. The secret document they try to decipher – and whose fragmentary nature anticipates the QAnon messages on 4chan – turns out to be a banal shopping list.

Wolfgang Iser

One year before the novel was published, Eco, a semiotician by profession, gave a lecture at the University of Konstanz on the “dispute of interpretations”. In this lecture, he called the concept that “texts can be interpreted to infinity” a “hermetic semiosis”, in the occult sense of that word. Foucault’s Pendulum tells such a hermetic semiosis as a novel. Eco gave his lecture at the faculty that had developed the literary “reader-response theory” in the 1970s. One of its core terms was Wolfgang Iser‘s concept of “blank spaces” or “gaps” (“Leerstellen”) in literary texts; inherent breaks and lack of information that readers have to mentally supplement, and through which meaning can only emerge in a dialogue between text and reader.

The QAnon text fragments push both hermetic semiosis and the blank space principle to their extreme and take, so-to-speak, reader-response theory into popular culture. The mantra of the QAnon movement as well as of the German Corona deniers is that it makes no final claims, but only gives critical thought-provocations, which everyone should research for themselves. Since the “research” of most QAnon followers consists of Google and YouTube searches within their own filter bubbles, they end up confirming their own assumptions and conspiracy-mythological world view, but with the feeling of having reached these conclusions through their own individual research.

This scavenger hunt principle makes QAnon an engaging interactive game. Its pull and its attraction is explained by this. In fact QAnon is an “Alternate Reality Game” (ARG). ARGs are a genre between computer game and group adventure, for which there has been a specialized game industry since the 1990s. They contain puzzles and mysteries that players solve by finding information outside the game and sharing it with other players. Alternate Reality Games often have open ends. As their name suggests, their game plots construct alternative realities that overlay the players’ everyday life and, so-to-speak, charge it with magic.

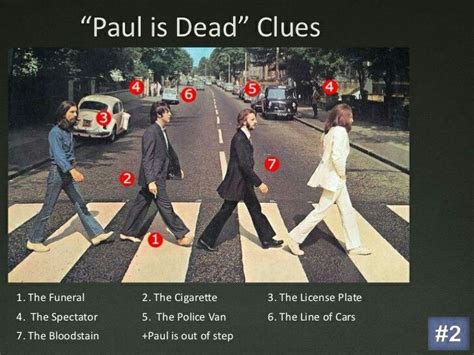

An early example of a conspiracy myth that already functioned as an alternate reality game is “Paul is dead” – the claim made in 1969 that the Beatle Paul McCartney died in a car accident three years earlier and was replaced by a doppelganger. A large subculture of American Beatles fans emerged around this myth, nicknamed “Cluesters”, who shared information via radio programs, local newspapers, fanzines and word-of-mouth. In song lyrics, on record covers and Beatles publicity material, they decoded supposed secret messages about McCartney’s death. It was an alternate reality game before the name existed, and a decentralized and self-organizing one at that. Its subculture still exists and even experienced a renaissance through the Internet since the 2000s.

An early example of a conspiracy myth that already functioned as an alternate reality game is “Paul is dead” – the claim made in 1969 that the Beatle Paul McCartney died in a car accident three years earlier and was replaced by a doppelganger. A large subculture of American Beatles fans emerged around this myth, nicknamed “Cluesters”, who shared information via radio programs, local newspapers, fanzines and word-of-mouth. In song lyrics, on record covers and Beatles publicity material, they decoded supposed secret messages about McCartney’s death. It was an alternate reality game before the name existed, and a decentralized and self-organizing one at that. Its subculture still exists and even experienced a renaissance through the Internet since the 2000s.

Many of the elements that make up QAnon today were already present here: “research”, paranoid overinterpretation of popular culture products to reveal a secret horrible truth, networking, obsessions with death and doppelgangers. Today QAnon followers spread the word that two years ago in Guantanamo Bay, Barack and Michelle Obama as well as Hillary Clinton were arrested, executed and replaced by clones.

Recently, American journalists and scholars have called QAnon a religion in the making. In families and in partnerships, dramas take place when individuals have drifted into QAnon’s parallel world. Even if Trump should be voted out of office, the belief and conspiracy myths of QAnon will not disappear. The end of his presidency would probably even fuel his messianic legend, rendering him a martyr and victim of the “Deep State” and the liberal establishment. A re-elected Trump could create more difficulties for QAnon to explain why salvation hasn’t happened yet. Already now QAnon is undergoing various metamorphoses. They could accelerate and result in a more mainstream version of the conspiracy myth.

Florian Cramer is professor for visual culture at Willem de Kooning Academy in Rotterdam.

Wu Ming 1 is a member of the Wu Ming collective of writers and cultural theorists in Bologna. His new book La Q di Qomplotto (“The Q in Qonspiracy”) will be published in February 2021.

Originally published, in German and in a shorter version, in Süddeutsche Zeitung on 30 October 2020.

_

FURTHER RESOURCES

ENGLISH. Wu Ming 1, The Q in Qonspiracy: QAnon and Its Surroudings. How Conspiracy Fantasies Defend the System. English translation of the Index.

FRENCH Wu Ming 1, Conspiration et fantasmagorie à l’ère de Trump et du Covid. Une enquête en deux parties, septembre 2020.

ENGLISH Wu Ming’s statements to Buzzfeed on Q, Luther Blissett and QAnon, full text, August 2018. First time QAnon was called an Alternate Reality Game?

ENGLISH Beyond The Paranoid Style. On Conspiracism, with focus on QAnon. A lecture held by Wu Ming 1 at McGill University, Montréal, Department of Languages, Literatures and Cultures, on September 20th, 2018.

ENGLISH Towards A Poetry of Debunking. Podcast: Henry Jenkins interviews Wu Ming 1 and Benjamen Walker, October 2018.

–

–

Scrivo qui, per comodità.

Se è vero che la parola complotto è usata ed abusata, soprattutto in questi recenti due anni pandemici, in questi giorni notizie “fresche” hanno in me riaperto delle considerazioni che voglio condividere con voi.

È di qualche giorno fa la dichiarazione di Palù, secondo la quale, riassumendo all’estremo, la probabilità che il virus del Sars COV 2 sia di origine animale senza l’aiuto dell’uomo è di 1 su un trilione (1/1000000000000000000). La “prova” sarebbe una particolare sequenza del genoma del virus. Ovviamente non credo che lo studio l’abbia fatto Palù -virologo, già presidente di Aifa- ma che si sia basato per tale dichiarazione a vari studi internazionali effettuati nell’ultimo periodo.

Ne abbiamo già discusso, qui su Giap.

Ovviamente questo argomento non deve servire come “scusa” all’intensificazione dello sfruttamento del globo e devastazione dei suoi ambienti naturali, credo ci debba aiutare a considerare con più consapevolezza la trasmissione e la condivisione delle conoscenze nella nostra società, ed eventuali punti critici (come del resto già sviluppato da Horkheimer ed Adorno una settantina di anni fa, nella società occidentale).

Che il virus non potesse essere creato dall’uomo è stato, per più di un anno, patrimonio culturale e scientifico della grandissima parte della popolazione (almenooccidentale) e degli esperti e scienziati. Chi vi si opponeva era un complotto/fascio/negazionista a seconda dei periodi (con spostamento semantico dell’uso di certi concetti ormai connotati storicamente), non si può prescindere da questo dato di fatto.

Come non si possa prescindere dal fatto che alcuni studiosi -subito bannati dalla credibilità internazionale- lo abbiano sostenuto con da quasi all’inizio (Montagnier per citarne uno tra i più noti), ma anche qui l’iter della richiesta di un dibattito di certi specialisti, con appelli anche internazionali sull’argomento, è vasto.

Da ultimo, per arrivare alla stretta attualità, la preoccupazione per gli Usa che certi laboratori biologici entrino in mani russe, a quanto pare, detto dalla Nuland (sottosegretario di stato per gli affari politici Usa).

In soldoni: siamo stati vittime per lungo tempo di un complotto?

Quali considerazioni se ne possono trarre andando a rileggere a ritroso questa pandemia? E cosa dobbiamo dedurre sul concetto di “verità condivisa” nella nostra società?

Si ricordi che il virus, a quanto pare, è presente in Italia quantomeno dal settembre 2019.

È di pochi giorni fa la notizia, girata in tutto il mondo, che secondo due studi nuovi di zecca l’epicentro della pandemia di Sars-Cov-2 non sarebbe stato nessun laboratorio bensì il mercato “umido” di Wuhan, con ogni probabilità per via del commercio di animali vivi infetti:

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/02/26/science/covid-virus-wuhan-origins.html

Dopodiché, ciascuno legga e si faccia la propria idea.

Detto questo, troviamo molto irritante questo appigliarsi a qualunque vecchio post – addirittura questo in inglese, rivolto a un pubblico non italofono! – pur di tirare avanti la discussione sul virus – facendola ricominciare sempre dagli stessi punti – in una fase in cui abbiamo detto che il blog è in difficoltà e non in grado di proseguirla.