This article appeared in the Italian daily paper L'Unità on January 18th, 2004: This article appeared in the Italian daily paper L'Unità on January 18th, 2004:

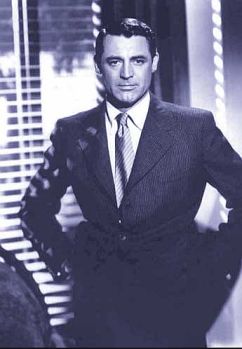

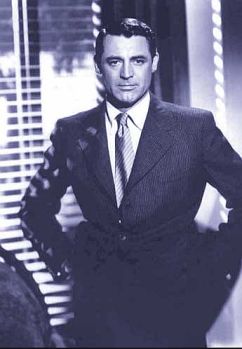

A Class Apart, that is: A Hundred Years of Cary Grant

by Wu Ming

Translated by Bianca Colantoni

Today is the centennial of Archibald Alexander Leach's birth, better known as Cary Grant. We'll never know if such an event had long been foretold by the constellations or whether it was anticipated by bizzarre events. Anyway, it was an important event for the following reasons.

Somebody will think that ours is an authentic obsession. As a collective, we mentioned this actor numerous times; we studied his life, his work and, above all, we placed him among the characters of our novel 54, which was inspired by an important but not well-known chapter of his biography: his collaboration with the British secret service to disclose nazi infiltration and sympathies within Hollywood.

It might be an obsession, but allow us to explain who he was and perhaps you'll understand.

Archie Leach/Grant was and is one of the most loved personalities of 21st century pop culture. Born in the English city of Bristol (his bronze statue can be admired in its Millenium Square), from a poor proletarian family, he was very young when he joined Bob Pender's circus and became an acrobat (in many of his films his somersaults and twists would be performed without a double). As the circus toured the USA, Archie decided to stay in New York City where he worked at many jobs. Most memorably, he worked as a sandwich-man on stilts. He worked in the theatre, acting small roles in a fewfilms, and eventually moved to California where he adopted the stage name with which he would become more than famous.

He began a long period of disciplined and meticulous creation of a new identity, a full-time job which his most sharp biographer, the englishman Graham McCann, calls “the invention of Cary Grant”. At the stage where he came out of his coccoon, he acted in various films without praise or blame until 1937, when he triumphed as the leading actor in The Awful Truth, a milestone in the so called screwball comedy.

In baseball, the term screwball is a spin shot. Figuratively speaking, it means something returning from the opposite direction of its starting point, thus the slang meaning: “screw”, “excentric”, “bizzarre”, “off one's head”. It was sentimental light comedy, frantic, with misunderstandings followed by dramatic moments, contrasts of personalities, and – in almost every film – chases and races against time. It was the main popular pastime of the Depression and it lasted until the end of the war.

Cary was screwball comedy personified, because in this genre it's the male leading actor of the film that sets the pace: besides The Awful Truth, there's Bringing Up Baby (1938), His Girl Friday (1940), The Philadelphia Story (1941) and I Was A Male War Bride (1949). Cary was helped by his ability to improvise, inherited from his circus years and from musical comedy (some of his comedies' best cues were out-of-script).

But mind you, Cary didn't only make you laugh: his “dark side” was explored by Alfred Hitchcock in Suspicion (1941), in the very famous scene of the glass of milk and in Notorious (1946), in which (a rare event) he gives us an introvert and icy acting.

Meanwhile, a shock brought him back to the past, to his previous identity: his mother, Elsie Leach, whom he thought dead since his childhood, as found in an asylum where his father (recently deceased) had locked her up. Archie/Cary, happy to have a mother again, moved her to a more confortable old-age home and for the rest of her life would hold her in the palm of his hand.

Within Hollywood's political economy, Cary was spokesman to an innovation: he was the first independent star, a freelance, outside the Studios' controls. Such an independence allowed him, amongst other things, to chose if and when to retire from the stage. At the beginning of the 50s, with the arrival of a new generation of actors (Brando, Dean, Clift), his star tended to dim and so he decided to step down.

After a year of whiteout, Hitchcock persuaded him to act in To Catch A Thief (1954).

At the end of the decade, Cary was the most important and most famous Hollywood actor, he was the one who had radically redifined the standards of male elegance: if the rigid three-piece suit had been replaced by suits without waistcoats, part of the merit went to the image he portrayed. He was a role model as far as style was concerned, standard bearer of a graceful, relaxed virility (in his films he is always the one who is seduced, never the seducer). By then he could do what he liked, even going as far as experimenting with drugs (he admitted to having taken LSD a hundred times) and acting in Father Goose (1964) in a (perfectly) shabby and dishevelled version. In 1966 he abdicated from acting. In 1970 he received the Oscar for his carreer. In 1986 he exited life as a legend.

On reviewing his life, Cary has become a sort of secular saint. Well-constructed fandom subcultures have flourished around the cult of his elegance, by mail or in film clubs in the past, nowadays on the Internet. There is a vast selection of web-sites (the most extensive is www.carygrant.net) and debating forums (Warbrides) proliferate. Cary belongs to that number of personae that defy time, becoming open icons, stories that create community bonds, transforming the quality of life of those who narrate and hand them down. In this way pop culture plays on some “prerequisites of communism” that the “apocaliptic” Left has often mistaken as elements of bourgeoise ideology or as a result of social brainwashing. Understanding Cary Grant's myth could be useful to face our present and thus find adequate strategies for human resistance.

McCann entitled the biography Cary Grant: a class apart. “Class” both meaning savoir faire and social class. The hard work of self-improvement, the obsessive self-discipline kept by the former Archie Leach enacting the character he had invented... This is all very "working class". It is a character, it better be repeated, whose nourishment is the continuous challenge in the social roles, in national identities, class and types. “Cary Grant” is a “trans-atlantic” character, a synthesis of Europe and America in continuous redefinition (his accent was undefinable). “Cary Grant” is no longer working class as Archie Leach was but he is neither upper or middle class. He is precisely a class apart. His masculinity is unmistakable, but – as stated above – it was very different from the solid one of the Clark Gables and Gary Coopers. In these times of ours, full of shit and dejection, during the sunset of a phase of a social conflict (the phase begun in Seattle in November 1999), it is more than important to re-discover non-chalance as an individual and collective fighting weapon.

Style is a martial art: the European working class knew it well in its own time. Show the bosses that - with a little inventiveness and with little cost - you can be more elegant and dignified than them. Photographs of First of May demonstrations or of Togliatti's funerals show proud looks and attitudes, perfectly ironed - even if a little worn out - suits, impeccably tied ties around well-starched collars; the women wear foulards with complex knots and their home-sewn dresses have a perfect cut. What stands out is the care for details, the love for cleanliness by those who have to sweat and get dirty every day. The message is more or less the following: “Bosses, what you behold are not animals or primitives, and the same care we take to prove it, we'll use it to fight against you".

This is how anti-mafia judge Giovanni Falcone describes Palermo's working-class during the 50s and 60s in his book Cose di cosa nostra [Men of Honour: The Truth about the Mafia]:

“I used to live in the old town centre, in Piazza Magione, in a building we owned. Nearby there were the catoi, damp rooms where the working-class used to live. It was a real spectacle seeing them on Sundays coming out of those holes, beautiful, clean, elegant, oiled hair, polished shoes, proud looks”.

Two years ago, after the publication of 54, it was a great satisfaction to receive the following comment from a female reader:

“My father, an active and militant comrade, primary schooling, great dancer, very poor, at the age of ten was already working in a factory, but in his simplicity he had a gentleman's bearing. This was also thanks to my mother who used to spend nights on end sewing shirts and suits that fit him perfectly. The shirt ironing was a ritual that still fascinates me. Heating the irons on the stove, not a gesture out of place nor a fold; a ritual that could never tire me. Dad's white shirt was to be ironed because the great transformation happened on Sunday morning. I used to sit on the bathroom's step, waiting for my father, he came out well shaven, combed and I watched while he dressed in his Sunday's best because he had to go to his party's branch to distribute the newspaper L'Unità. He left the house happy, most elegant, his silk handkerchief in his breast pocket matching the tie and the polished shoes. The suits were always the same, but this was just trifle to him”.

A similar attitude can be found in afro-american culture (another element to consider in the class-“race” relationship). Lloyd Boston, author of Men of Color: Fashion, History, Fundamentals (1998), writes:

“For Black American men in particular, clothing has always served a symbolic purpose. What we wear signals what we are and, more important, what we want to be. Whether the look is tough, affluent, Afrocentric, or preppie, our sartorial skill is also a survival skill”.

Of his own, Cary has added something fundamental: lightness. Not the Coca Cola or the Philadelphia “lightness”, nor the “lightness” meant as superficiality, but the lightness meant by Calvino in his Lezioni Americane (American Lessons), the lightness that helps to flee from the world's sloth and dullness and is associated “with precision and determination, not with laxity and vagueness”.

A hundred years ago, in Bristol, a man was born. He was destined to leave a mark. |