/Giap/digest #1 – From Italy to Indochina – November 5th, 2000

From La Repubblica (Italian daily paper), Saturday, 21 october 2000, the whole frontpage of the "Cultura" section :

THE VIETCONG WHO LIVES

IN ROMAGNA

The new novel of the ex-Luther Blissetts

by Michele Smargiassi

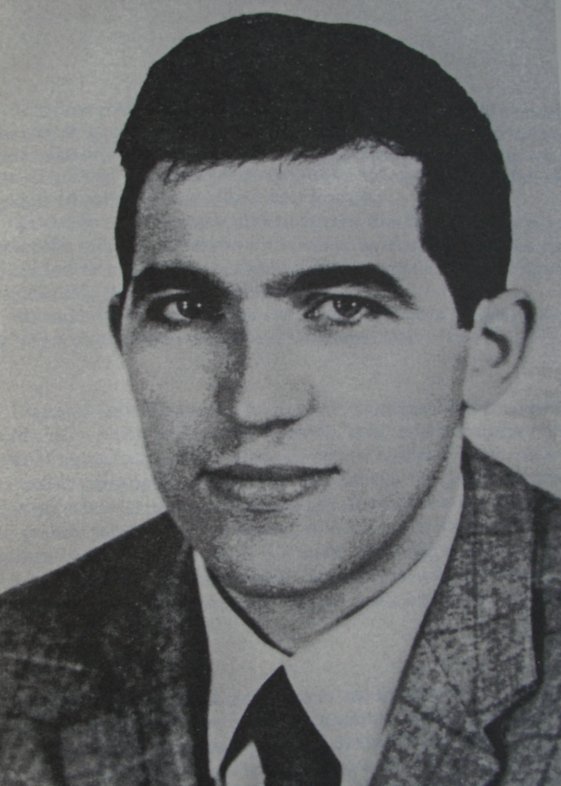

Comrade "Gap"

has not slept alone for thirty-two years. Every night, hundreds of faces keep

him company, almond-eyed faces in the dark green of the jungle, mud-covered

and frowning, they scream and torment him. "I killed too many men".

The quiet countryside near Imola, with its neat vineyards, does not bear

any resemblance to the forests of Indochina, and Vitaliano Ravagli looks like

a peaceful man, a 66-year-old man in very fine fettle ("My punch is still

like a hammer blow"). This is a land of bull-men, generations of peasants

with big shoulders.

Nothing reveals that this man was a Vietcong. A romagnolo vietcong,

a restless communist who embarked twice (in 1956 and 1958) on the mysterious

routes of socialist internationalism, went to Laos and fought "the fascists

down there".

Ravagli pours some sherry from a bottle with cyrillic words on the label.

"You don't believe me. I don't give a damn. I could tell you about my

wounded leg, or the eye I lost, but I don't care. Me, I know what I lived

through."

He lived through eight months whose account sounds like a novel. In fact,

one reads "novel" under the title Asce di guerra [Axes of

War] (Marco Tropea Editore, pp. 376, 29,000 lire). It is the second work by

the former Luther Blissett quartet, i.e. the authors of the best-seller Q

[...] who have now adopted the name "Wu Ming" ("no name"

in chinese).

They believed Ravagli, whom they met almost by chance while they were working

on another ambitious tale, 54 (which is set in the 1950's as well).

"In Imola there's a man with an amazing story", said crime novel

author Carlo Lucarelli. He introduced them, they met up with him, had dinner

and spent the night listening to that sparkling testimony. At last, they decided

to write a book all together, a really strange book indeed, which is described

as a "novel" for the punter's convenience, but is a narrative

object mixing fact and fiction, careful historical research and more unembarrassed,

"free and easy" accounts. Just like Q, as far as the style

is concerned. Against Q (indeed, against the success of Q),

as regards the rest.

Wu Ming constructed a plot with a strong emotional impact, un-sterilized by

the historical distance. The plot surrounds Ravagli's true story. Asce

di guerra unburies the stories of (real) uncompromising Partisans, disappointed

post-war rebels, "those who kept firing".

The novel makes a clean sweep of the Resistance's hagiography, of the Partisan

as a "good guy". The re-emerging rudeness has a stunning effect

on the (fictitious) attorney Daniele Zani, who lives in the present-day once-"red"

Bologna. Zani - a nephew of partisans himself - is also acquainted with squatters

and counsels the defense of migrants and social outcasts.

The short-circuit between the Resistance, anti-Imperialism and the "spirit

of Seattle" re-opens a closed, untouchable folder, i.e. that of post-war

"Reconciliation", the "back-stabbed Resistance", the "stolen

revolution" and so on. All this was the subject of a fierce controversy

on "post-war assassins" in the early Nineties.

This book is a deliberate "outrage against the present" and its

removed aspects. History (and memory) is an "hatchet of war" to

be unburied.

Ravagli, however, never buried his own hatchet : "My hate is as sharp

as it was in my teens". "Hate" is the word he uses more often

during the two-hour long interview. He gave himself a war name ("Gap")

[1], although he was just a little kid in 1944, too young

to join the Partisans. The "Paths of Hate" took that boy to Laos.

He hated because his family ("the poorest family in Imola") starved

for years and was massacred by tubercolosis ("It's worse than Aids").

He hated the fascist Black Brigades ("Worse than the Germans"),

the "snitches" and "the bakers who put chalk in the dough".

After the Liberation, he did not stop hating: "The 'comrades' would come

to the Bar Nicola - which the police called 'the Kremlin' - to show off on

their new scooters, while my family was still starving."

An unescapable hate, a weapon and the will to use it: "I would've done

anything to kill a fascist". Some did it, long after the end of the war.

Gap chose a different way, the most unexpected and dangerous one, which took

him eighteen thousand kilometres away.

"In Milan there was a den of comrades along the Navigli riverside. Teo,

a friend of mine, told me about them. Teo was a Partisan who hadn't been brainwashed.

The Italian Communist Party had nothing to do with them, indeed, the aim was

to 'train' comrades to revolutionary tasks, send them to Indochina. When they

came back, they'd get rid of all the comrades whose asses were glued to their

chairs. I introduced myself, they accepted me."

A few days later the 22-year-old Ravagli received the call-up notice from

the Italian army, and became a draft dodger. A boat. An escape to Yugoslavia.

An aircraft. Eight days of training at some place in central Asia. Another

flight. At last, the jungle. "We were 17 men from Milan, Bari and other

towns. I think I'm the only survivor." Which means that nobody can corroborate

his words. "I said I don't care whether you believe me or not".

Who were the Milan-based comrades? "I just can't tell you". A network

organizing international brigades for Vietnam, and no-one had a clue? "Believe

me or not, it makes no difference to me."

The jungle and a firearm: a Bren sub-machine gun. The mission: to escort the

early few convoys of "red ants" supplying the embryonal guerrilla

organizations in South Vietnam. The commander: a chinaman named Li, "a

veteran of the Long March, a hard-skinned strategist who wept for his dead

men after every attack."

He did not find much internationalist spirit though: "They divided us

into different groups. They didn't like us, nor did they understand why we

wanted to fight in somebody else's war. They thought we were crazy. Some of

us were wretches, they ended up with us but might as well join the Foreign

Legion."

They were inexistent fighters in a secret guerrilla warfare, the war in Laos,

which was obscured and absorbed by the more famous Vietnam war.

They were organized into irregular squads, the extremist ones backed by China,

indifferent to the truces and overturns of an incredibly confused situation.

"It was a tribal war", Gap whispers. The French military advisors

helped the government' army, but did not fight. The Americans were going

to replace the French, but had not yet taken the field. "Our foes were

the indigenous Meos [2], gangs of boys, even little kids,

as fierce as beasts, they would kill, rape, burn people alive."

Ravagli became a guerrilla to "kill fascists" and soothe himself.

"Mine was a personal war, I killed because I wanted to make a point to

myself." He found himself in a sea of blood: "We were high on adrenalin

and something else, we were killing machines, no ideology, it was about killing

or being killed." Four months of hell in a heaven-on-earth of unknown

animals and plants, until, during a lucid interval, Ravagli decided (and managed)

to return to Italy.

Back home, the army punished him for his desertion, putting him in a disciplinary

corp. After his national service, he returned to Imola. Soon he felt like

a stranger, a misfit. "I had killed, I couldn't be an ordinary man anymore."

The same old bar. A trivial everyday life. The meagre pre-boom welfare. "I

was going crazy, I might get into serious trouble." He left again, at

the service of uncle Ho Chi Minh, same route, same destination.

This time is even worse: marches in the mud, illness, poison snakes, assaults

on opium convoys, blood, death, till ravagli got beyond all bounds and realized:

"I am a communist, not an assassin."

A farewell to arms, Gap goes back home. Apocalypse now is over.

The epilogue,

thirty years in a few words: some women, a son and a daughter, an unlucky

commercial enterprise, and a pension amounting to 717,000 lire [3].

A Vietcong on minimum welfare, with a wonderful story which nobody deserved

to hear, "Not even the ANPI comrades, whose only worry was the choice

of a restaurant after the marches on April 25th [4]."

The heart full of bitterness, no revolution brought back home. Later, he did

not support those younger boys who wanted to "be like the Partisans":

"Somebody from the Red Brigades - though it could be the secret service

- tried to contact me. I told them that the revolution starts from the grassroots,

and when it shoots, it must aim high." Everything was over, everything

but the hate. "I never stopped hating the people who starved us and let

us die. Now the old ones are dead, but the new ones aren't different. I don't

deny myself, I've been hating them for half a century, from dawn till dusk."

However, from dusk till dawn, the jungle ghosts take their revenge.

1.

GAP = Gruppi di Azione Patriottica [Patriotic Action Groups], anti-nazi urban

guerrillas in the Italian liberation war (1944-45).

2. A despicative hmong term for "savages", by which

Tubi Lifung's "red" Hmongs called their CIA-backed ethnic fellows

commanded by Vang Pao.

3. About 358 Euros, or 315 US dollars (change rate: November

5th, 2000).

4. The Anpi is the National Partisan Association, April 25th

is the anniversary of the Liberation (1945).